Groundings

By Jackie and Noel Parry

Groundings occur more often than you think, given today’s reliance on electronic navigation aids. A grounding can commonly be the result of incorrect use of digital charts (wrong scale usually), insufficient paper chart backup, poor route planning, fatigue, and lack of appropriate look-out.

Groundings or strandings are the unintentional contact with the seabed. These can occur suddenly without warning.

A stranding can be avoided by navigating with caution and keeping a regular check on your position. Remember safety is the most important aspect when planning and undertaking a voyage. And unless you zoom in on every screen on electronic charts, you could miss a rock, reef, a partial or submerged object. Refer to paper charts when route planning.

Maintain Watertight Integrity

Watertight integrity can be breached through any activity or event that allows the ingress of water in unwanted areas of the vessel.

Examples include damage caused by collision, grounding, or heavy weather.

What to do first

Raise the Alarm

If you go aground, for any reason, the first thing you must do is raise the alarm. This is the number one priority in any emergency situation.

That doesn’t mean activating the EPIRB straight away; assess the situation, inspect the bilge. Let someone know what is happening. It may a quick fix, but it may not. The situation could snowball quickly and then there may not be time to call for help. Once the situation has been remedied you simply pass on this information to the person/organisation you alerted in the first place.

Failure to cancel your Securite alert may endanger the lives of others who have assumed you are in distress.

If you don’t let them know that all is well, they will try to reach you and organise some help. If your emergency is out of control this could save your vessel and even your life.

What next?

Next secure the vessel, ensure you have a safe platform to work on and that you can stay there (depending on location and weather) for as long as needed.

For example, if you are on a falling tide, transfer as much weight as you can into the bottom of the vessel and try to deploy the ground tackle to stabilise the boat.

If you are in a seaway and you are not ready to move, stabilise your boat by laying out anchors and if you can completely fill or completely empty tanks, this prevents the effects of liquid mass sloshing side to side creating an imbalance, this is commonly referred to as ‘Free surface effect’.

Sometimes it is possible to remove the vessel from a grounding almost immediately, depending on the tide, sea, and type of vessel. For example, if you go aground at the very bottom of the tide and the conditions are calm (and you were making way slowly at the time of the grounding) the vessel should reverse easily. Or there may be a quick way to deploy the anchor (via the dinghy) in the right position so you can kedge off. A sailing boat may be able to lift their keel or induce a heeling moment by raising a sail to leeward thus raising the keel from the seabed. Even swinging out a weighted boom may be sufficient to swing the keel up and off. You should try to prevent being driven further onto the reef whenever possible.

If you do manoeuvre your boat off the bottom quickly, carefully check the hull and bilges for damage and/or water penetration before proceeding with your trip. If severe damage has occurred and you are sinking, it may be prudent to deliberately run the vessel aground again, preferably in a location that allows the crew to evacuate safely.

But We’re Stuck!

If you can’t immediately free your boat and you are stuck, stabilise the vessel as per above and assess the situation

- What’s the sea-state?

- Is there a swell?

- Is night approaching?

- Is there bad weather approaching?

- Is the tide rising or falling?

- Are you in a dangerous position – i.e. busy seaway?

Each of one these questions will help you form a plan. Obviously if you can manoeuvre your vessel off the seabed, do so straight away. If you have to wait for the tide to rise and night is approaching and you are in a busy seaway, alert local vessels with a Securite message and organise appropriate lighting.

With bad weather approaching – assess your location, strength of vessel, ability to stabilise and ability to ask for a rescue tow, are all considerations.

Echo Sounders

Echo sounders can be fitted with alarms to notify you when you are in shallow water. You should, however, be monitoring your sounder and position carefully and constantly when in shallow water.

Most echo sounders can be adjusted so that the depth of water is shown and not just the under keel depth.

If your sounder is set with the underkeel depth then the draught of your boat must be added to the sounding to arrive at the depth of water.

Tide will also have to be taken into account to adjust the sounding shown on the display so as to correspond with the charted depth.

Multicoloured Displays

On multicolourd displays, different colours represent various signal strengths for returning echoes. This makes it possible to identify the reflecting properties, and therefore composition, of the seabed.

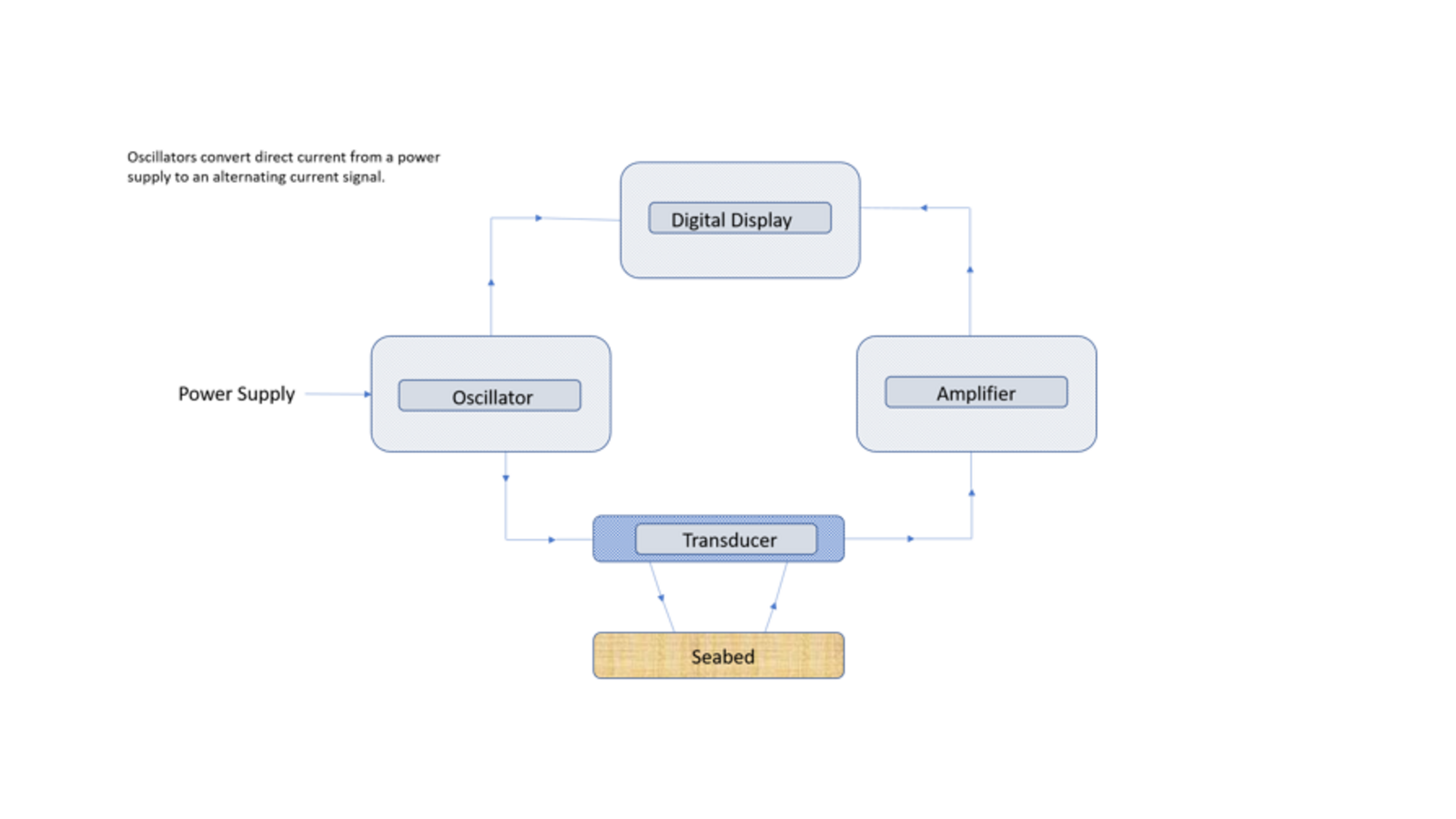

Echoes Echo sounders usually consist of an oscillator, transducer, amplifier and recorder/display. Oscillators convert direct current from a power supply to an alternating current signal, i.e. short electrical pulses. A small part of the pulse is fed to the display to indicate the zero base. The major part of the pulse is passed to the transducer which is usually sited on the bottom of the hull. The pulse is transmitted from the transducer as ultrasonic vibrations in a downward direction. The interval between the transmission and subsequent reception of the reflected pulses is measured and indicated in terms of depth on a display.

Variable Amplifiers

Within the circuit is a variable amplifier. The signal for greater depths need to be amplified. Signals returning from shallow depths need little amplification. If the amplification is too high you may receive multiple echoes.

Positioning of the Transducer

The transducer should be located in the optimum position in the vessel’s hull to receive the maximum benefit. The main problem with positioning is due to the aeration in the bubble train beneath the vessel. This aeration usually comes from the propeller, bow wave or underwater hull projections. Experiments show that the best position is from one quarter to one third of the vessel’s length from the bow.

Multiple Echoes

With a hard sea bottom and maximum sensitivity especially in shallower waters, there are often numerous echo lines visible. This is due to the pulses being reflected a number of times between the sea bottom and the hull or surface of the water. Reducing the gain will help remove these.

Second Trace Return

This may occur in deep water during the time the first pulse is on its way to the seabed and back, the transducer has sent a second pulse, and while open to receive this second pulse, receives the original pulse. It will be displayed as though it was from the later (second) pulse, and at a much shallower depth than the seabed.

Uneven Trace

This occurs when the vessel is in rough seas and moving over a smooth seabed. It is caused by the vessel pitching, giving rise to the apparent up and down movement of the seabed. The minimum reading should be taken as the depth.

Bottom Interpretation

- Mud often produces a weaker echo.

- A smooth bottom is usually mud or sand.

- A sudden steep change in depth is likely to be coral or rock.

- A hard or rocky bottom can give rise to second and third echoes.

- Mud overlaying hard rock can provide separate echo lines.

Paper Chart Information

A chart will show the depth of water by soundings and depth contours, shoreline, topographic features, nature of the bottom, tidal streams, magnetic variation etc., for the area, as well as:

Authority: The publisher that is responsible for the chart. e.g. NOAA, British Admiralty, Australian Hydrographic Service.

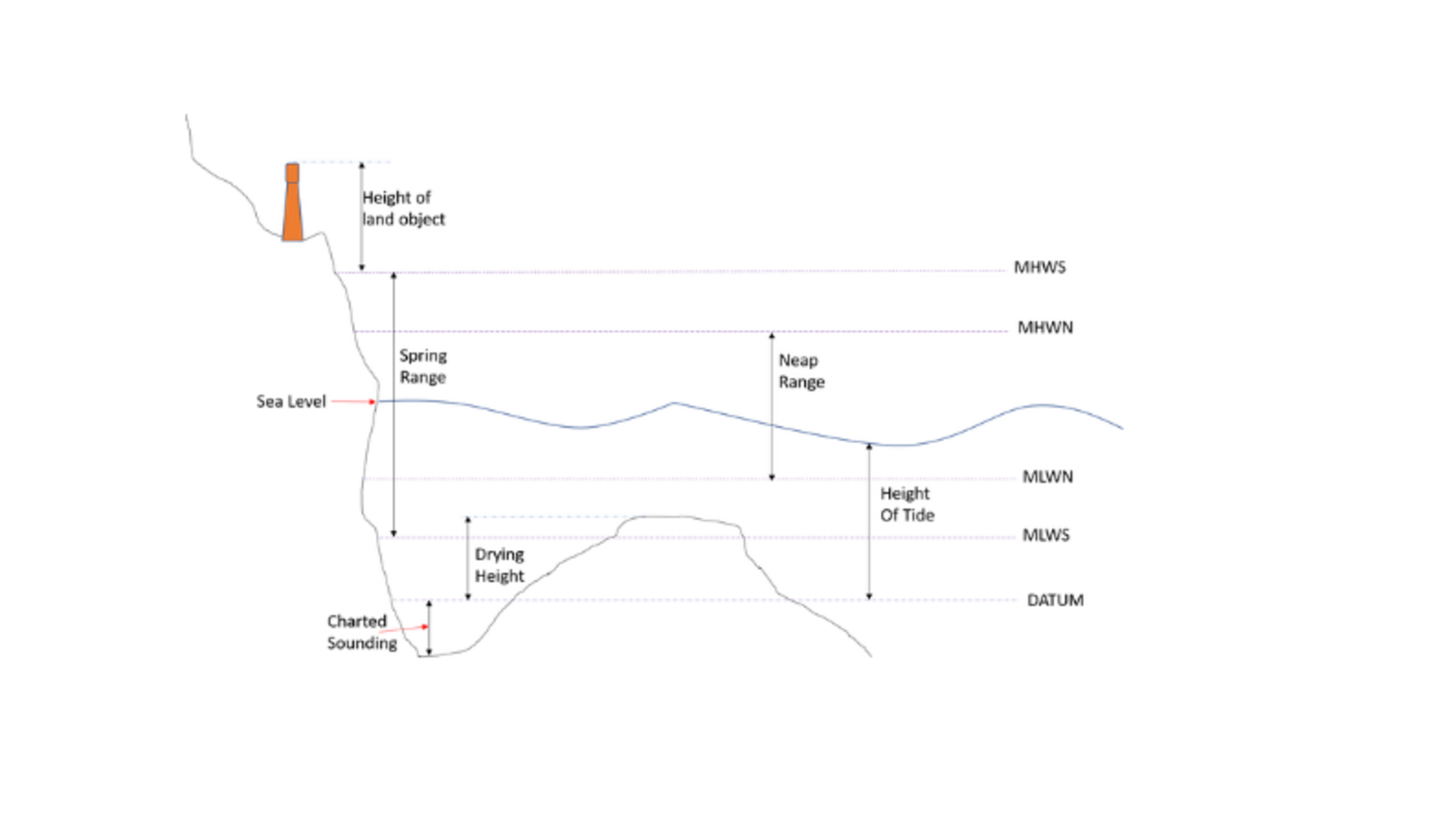

Depths: reduced to Chart Datum, which means they use the datum of the Lowest Astronomical Tide (LAT). The Lowest Astronomical Tide is the lowest levels which can be predicted to occur under average meteorological conditions.

Note: LAT is not the lowest level that may be reached as storm surges may cause considerably lower levels to occur.

Soundings and drying heights: Soundings are given below Chart Datum; Drying heights are given above Chart Datum. See image below:

Breakout boxes

Securite: The safety alert

Securite (“say-cure-i-tay”) is used when conveying useful information, including potential safety risks, navigation hazards or weather warnings.

Pan-pan: The urgency alert

Pan-pan (“pahn-pahn”) indicates that a vessel or a person on board needs assistance but is not in immediate danger.

Mayday: The distress alert

Thought to originate from the French “m’aidez” (help me), mayday means a vessel or person is in grave or imminent danger and signifies a request for immediate assistance. Mariners hearing mayday calls should immediately cease traffic on Channel 16 and stand by for further information.

Rule 30

Anchored vessels and vessels aground

(a) A vessel at anchor shall exhibit where it can best be seen:

i. In the fore part, an all-round white light or one ball;

ii. at or near the stern and at a lower level than the light prescribed in sub-paragraph

iii. an all-round white light.

(b) A vessel of less than 50 metres in length may exhibit an all-round white light where it can best be seen instead of the lights prescribed in paragraph (a) of this Rule.

(c) A vessel at anchor may, and a vessel of 100 metres and more in length shall, also use the available working or equivalent lights to illuminate her decks.

(d) A vessel aground shall exhibit the lights prescribed in paragraph (a) or (b) of this Rule and in addition, where they can best be seen:

i. two all-round red lights in a vertical line;

ii. three balls in a vertical line.

(e) A vessel of less than 7 metres in length, when at anchor, not in or near a narrow channel, fairway or anchorage, or where other vessels normally navigate, shall not be required to exhibit the lights or shape prescribed in paragraphs (a) and (b) of the Rule.

(f) A vessel of less than 12 metres in length, when aground, shall not be required to exhibit the lights or shapes prescribed in sub-paragraphs (d) (i) and (ii) of this Rule.

You Must Slow Down in Shallow Water!

Smelling the Bottom (aka Smelling the Ground, or Squat)

Smelling the Bottom Is a hydrodynamic explanation for squat. And squat is when water squeezes between the bottom of the boat and the seafloor. This creates an area of low pressure and the vessel sinks, or squats, into it. So the boat rides deeper in the water. Technically speaking, the vessel does not increase its draft — the waterline stays the same. However, the water immediately surrounding the vessel assumes a lower level. This will result in the vessel touching the bottom where it should not (according to depth).

The effect is heightened by speed – slow down!

So how far does a vessel squat? That is depended on the vessel’s draft and the depth of water that draft is in. Sea state is also a factor, when you are in a trough you are in less water.